Anaphylactic+Shock-+Pathophysiology,+Recognition,+and+Treatment.pdf

There is document - Anaphylactic+Shock-+Pathophysiology,+Recognition,+and+Treatment.pdf available here for reading and downloading. Use the download button below or simple online reader.

The file extension - PDF and ranks to the Documents category.

Tags

Related

Comments

Log in to leave a message!

Description

Anaphylactic Shock: Pathophysiology, Recognition, and Treatment Roger F Johnson, MD 1 and R Stokes Peebles Jr, MD 1 ABSTRACT Anaphylaxis is a systemic, type I hypersensitivity reaction that often has fatal consequences Anaphylaxis has a variety of causes including foods, latex, drugs, and hymenoptera venom Epinephrine given early is the most important intervention Ad- junctive treatments include fluid therapy, H 1 and H 2

Transcripts

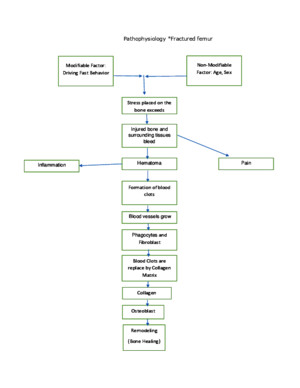

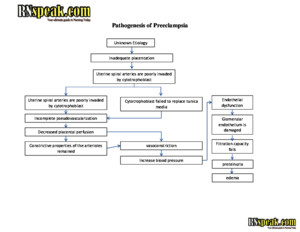

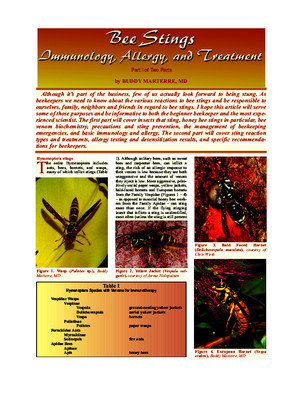

Anaphylactic Shock: Pathophysiology,Recognition, and Treatment Roger F Johnson, MD 1 and R Stokes Peebles Jr, MD 1 ABSTRACT Anaphylaxis is a systemic, type I hypersensitivity reaction that often has fatalconsequences Anaphylaxis has a variety of causes including foods, latex, drugs, andhymenoptera venom Epinephrine given early is the most important intervention Ad- junctive treatments include fluid therapy, H 1 and H 2 histamine receptor antagonists,corticosteroids, and bronchodilators; however these do not substitute for epinephrinePatients with a history of anaphylaxis should be educated about their condition, especially with respect to trigger avoidance and in the correct use of epinephrine autoinjector kitsSuch kits should be available to the sensitized patient at all times KEYWORDS: Anaphylaxis, epinephrine, shock, allergy Objectives: After reading this article, the reader should be able to: (1) discuss the pathophysiology of anaphylactic shock; (2) recognizeanaphylactic reactions; and (3) summarize the essential steps in treatment of anaphylactic shock Accreditation: The University of Michigan is accredited by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education to sponsorcontinuing medical education for physicians Credits: The University of Michigan designates this educational activity for a maximum of 1 category 1 credit toward the AMAPhysician’s Recognition Award A naphylaxis is a systemic, type I hypersensitivity reaction that occurs in sensitized individuals resulting inmucocutaneous, cardiovascular, and respiratory manifes-tations and can often be life threatening Anaphylaxis was first described in 1902 by Portier and Richet whenthey were attempting to produce tolerance in dogs to seaanemone venom Richet coined the term aphylaxis (fromthe Greek a, against, –phylaxis protection) to differenti-ate it from the expected ‘‘prophylaxis’’ they hoped toachieve The term aphylaxis was replaced with the term anaphylaxis shortly thereafter Richet won theNobel Prize in medicine or physiology in 1913 for hispioneering work 1 Anaphylaxis occurs in persons of all ages and hasmany diverse causes, the most common of which arefoods, drugs, latex, hymenoptera stings, and reactions toimmunotherapy Of note, a cause cannot be determinedin up to one third of cases 2–4 Anaphylactoid reactionsare identical to anaphylaxis in every way except theformer are not mediated by immunoglobulin E (IgE)Common causes of anaphylactoid reactions includeradiocontrast media, narcotic analgesics, and nonsteroi-dal antiinflammatory drugsSigns and symptoms can be divided intofour categories: mucocutaneous, respiratory, cardiovas-cular, and gastrointestinal Reactions that surpass Management of Shock; Editor in Chief, Joseph P Lynch, III, MD; Guest Editors, Arthur P Wheeler, MD, Gordon R Bernard, MD Seminars in Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine , volume 25, number 6, 2004 Address for correspondence and reprint requests: Roger F Johnson, MD,Center for Lung Research, T-1217 MCN, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, 1161 21 st Ave South, Nashville, TN 37232-2650 E-mail:rogerjohnsonvanderbiltedu 1 Division of Allergy, Pulmonary, and Critical Care Medicine, Department of Medicine, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville, Tennessee Copyright # 2004 by Thieme Medical Publishers, Inc, 333 Seventh Avenue, New York, NY 10001,USA Tel: +1(212) 584-4662 1069-3424,p;2004,25,06,695,703,ftx,en;srm00340x 695 D o w n l o a d e d b y : U n i v e r s i t y o f W i s c o n s i n - M a d i s o n C o p y r i g h t e d m a t e r i a l mucocutaneous signs and symptoms are considered to besevere, and, unfortunately, mucocutaneous manifesta-tions do not always occur prior to more serious mani-festations Mucocutaneous symptoms commonly consistof urticaria, angioedema, pruritis, and flushing Com-mon respiratory manifestations are dyspnea, throattightness, stridor, wheezing, rhinorrhea, hoarseness,and cough Cardiovascular signs and symptoms includehypotension, tachycardia, and syncope Gastrointestinalmanifestations include nausea, vomiting, abdominalcramps, and diarrhea 2,3,5,6 First-line treatment of anaphylactic shock is epi-nephrine Other adjuvant treatments are often also used;however, there is no substitute for prompt administra-tion of epinephrineA century has passed since the discovery of anaphylaxis, and much knowledge has been added toour understanding of this syndrome This article reviewsthe pathophysiology, recognition, and treatment of ana-phylactic shock SCOPE OF THE PROBLEM For several reasons the incidence and prevalence of anaphylaxis are unknown Notably, because anaphylaxisis not a reportable event, no national registry exists tomaintain statistics concerning anaphylactic reactions Inaddition, the lack of a standard definition and misdiag-nosis by health care personnel hampers efforts to de-scribe the frequency and severity of anaphylaxisFurthermore, many people that suffer mild reactionsnever seek medical treatment Finally, attempting toextrapolate data from small, nonstandard patient popu-lations to a national scale is fraught with problems 2,3 The Rochester Epidemiology Study provides thebest characterization of anaphylaxis in the UnitedStates 3 This computerized, indexed database containsmedical records from residents of Olmsted County,Minnesota Because of this registry, the residents of Olmsted County have been the subjects of multipleepidemiological studies that are believed to most accu-rately depict the situation nationally Important points tonote, however, are that Olmsted County is 95% whiteand has a higher representation of health care workersthan the general population The Rochester Epidemio-logic study yielded 154 separate anaphylactic reactions in133 residents between 1983 and 1987 This translatedinto a 30/100,000 person-year occurrence rate and a 21/100,000 person-year incidence rate of anaphylaxis Themost common symptoms and signs were cutaneous(100%), respiratory (69%), oral and gastrointestinal(24%), and cardiovascular (41%) Anaphylaxis wasmore common in the summer months (July–September)and episodes were equal among males and femalesEpisodes were temporally related to suspected triggersbetween a few minutes to 2 hours Atopy was present in53% of those experiencing anaphylaxis and an allergy consultation was obtained in 52% The hospitalizationrate was 7% and the case fatality rate was 091% (onepatient out of 133 expired) 3 When projected to theentire US population on an annual basis these numbersare significantNeugut et al sought to improve understanding of the epidemiology of anaphylaxis by surveying the med-ical literature 2 They estimated that between 33 and 43million people in the United States (based in 1999population estimates of 272 million) are at risk foranaphylaxis In addition, they estimated that between1453 and 1503 people die each year from anaphylactic oranaphylactoid reactions (due to food 100, penicillin 400,radiocontrast media 900, latex 3, stings 40–100) Lim-itations of this study include underreporting, misdiag-nosis, and failure to recognize cases of anaphylaxis by health care providers 2 Regardless, these numbers show that anaphylaxis is a serious health problem in theUnited States PATHOPHYSIOLOGY Anaphylactic and anaphylactoid reactions result fromsystemic release of mediators from mast cells and baso-phils Again, anaphylactoid reactions are chemically andclinically indistinguishable from anaphylactic reactionsexcept that they are not IgE mediated These mediatorsconsist of preformed substances stored in the granules of mast cells and basophils (eg, histamine, tryptase, he-parin, chymase, and cytokines), as well as newly synthe-sized molecules that are principally derived from themetabolism of arachadonic acid (eg, prostaglandins andleukotrienes) 4 Anaphylaxis occurs in an individual after reexpo-sure to an antigen to which that person has produced aspecific IgE antibody The antigen to which one pro-duces an IgE antibody response that leads to an allergicreaction is called an allergen The IgE antibodies pro-duced may recognize various epitopes of the allergen These IgE antibodies then bind to the high-affinity IgEreceptor (Fc e RI) on the surface of mast cells andbasophils Upon reexposure to the sensitized allergen,the allergen may cross-link the mast cell or basophilsurface-bound allergen-specific IgE resulting in cellulardegranulation as well as de novo synthesis of mediators 7 Histamine is thought to be the primary mediator of anaphylactic shock Many of the signs and symptoms of anaphylaxis are attributable to binding of histamine to itsreceptors; binding to H 1 receptors mediates pruritis,rhinorrhea, tachycardia, and bronchospasm On theother hand, both H 1 and H 2 receptors participate inproducing headache, flushing, and hypotension 4 In addition to histamine release, other importantmediators and pathways play a role in the pathophysiol-ogy of anaphylaxis Metabolites of arachadonic acid, 696 SEMINARS IN RESPIRATORY AND CRITICAL CARE MEDICINE/VOLUME 25, NUMBER 6 2004 D o w n l o a d e d b y : U n i v e r s i t y o f W i s c o n s i n - M a d i s o n C o p y r i g h t e d m a t e r i a l including prostaglandins, principally prostaglandin D 2 (PGD 2 ) and leukotrienes, principally leukotriene C 4 (LTC 4 ), are elaborated by mast cells and to a lesserextent basophils during anaphylaxis and, in addition tohistamine, are also thought to be pathophysiologically important 8,9 PGD 2 mediates bronchospasm and vascu-lar dilatation, principle manifestations of anaphylaxisLTC 4 is converted into LTD 4 and LTE 4 , mediators of hypotension, bronchospasm, and mucous secretion dur-ing anaphylaxis in addition to acting as chemotacticsignals for eosinophils and neutrophils 8,9 Other path- ways active during anaphylaxis are the complementsystem, the kallikrein–kinin system, the clotting cascade,and the fibrinolytic system 8 Specific lymphocyte subtypes (CD4 þ Th2 T-cells) are central in the induction of the IgE responseCD4 þ T-cells are segregated into either T-helper 1(Th1) or Th2 types, defined by the cytokine profileproduced by the individual T cell Th1 cells are impor-tant in cellular immunity and make interferon gamma Th2 responses are important in humoral immunity andcritical for the allergic response Cytokines produced be Th2 cells include interleukin (IL)-4, IL-5, IL-9, and IL-13 10 Of great importance, IL-4 is the isotype switchfactor for B cells to begin producing IgE 10 The IgEresponse is thought to be an overly robust immuneresponse in certain predisposed (atopic) individuals 10 Multiple factors influence whether one produces a Th2 versus a Th1 response including genetic variables, en- vironmental factors, and triggers The hygiene hypoth-esis suggests that exposure to microbes in infancy leadsto ‘‘immune deviation’’ from a Th2 response, whichpredominates in utero, to a predominantly Th1responseLack of this ‘‘immune deviation’’ leads to further perpe-tuation of the Th2 response to allergens Stimuli (mi-crobes) that lead to a Th1 response cause IL-12 to beproduced by antigen-presenting cells IL-12 not only perpetuates the Th1 response but inhibits IgE produc-tion Furthermore, cytokines such as interferon gamma(produced by Th1 cells) and IL-18 (produced by macro-phages) suppress production of IgE Thus the Th1response is considered to be inhibitory to allergy 10 The incidence of allergic diseases is on the rise inthe United States 2,10 There are several potential reasonsfor this observation Diet may play a role because new allergens are increasingly being introduced into theAmerican diet For example, the United States is thethird largest consumer of peanuts in the world, 40% of consumption is accounted for by peanut butter 11 Furthermore, the dramatic increase in the use of latexproducts, particularly gloves, in the past 20 years has alsobeen implicated Finally, some invoke the ‘‘hygiene’’hypothesis for the increase in the prevalence of allergicdisease 10 The basis of this hypothesis is that inhabitantsof Westernized countries are exposed to fewer (ordifferent) immunologic challenges during immunesystem development, which leads to less stimulation of the Th1 pathway DIAGNOSIS Diagnosis of anaphylaxis in the acute setting is a clinicalone and starts with a brief, directed history becausetreatment must be rendered quickly This history shouldinclude questions regarding a previous history of atopy oranaphylaxis, and exposure to new foods, medications,and insect bites or stings Due to the varied presentationof anaphylaxis, it is often not recognized or misdiag-nosed Other conditions that mimic anaphylaxis include vasovagal events, mastocytosis, pheochromocytoma, car-diac arrhythmias, scromboid poisoning, panic attacks,and seizures 5,12,13 Evaluation should focus on manifes-tations that are likely to be life threateningThis includesevaluation of the respiratory and cardiovascular systems with particular attention to signs and symptoms of airway compromise and impending cardiovascular col-lapse 5 See Table 1 for common manifestations and theirfrequencyAfter or while the patient is being stabilized, acomplete history should be obtained Exposure history prior to the reaction is paramount and must includefoods, drugs, stings, or other agents The time course of events is also important because anaphylactic episodesusually occur shortly after exposure to a trigger; however,manifestations may be delayed by minutes to hours 3,5 Inanaphylaxis induced by foods, this delay is presumably attributable to the timebetween ingestion and absorptionof the offending allergen 8 In general, it has been ob-served that the faster the onset of manifestations, themore severe the reaction 2,5 Although history is essential,it is important to note, however, that anaphylaxis may bethe presenting manifestation of hypersensitivity; there-fore, lack of previous history of allergy does not rule outanaphylaxis Atopic persons, as one might imagine, arepredisposed to develop anaphylaxis Asthma, although apredictor for more severe reactions, is not recognized tobe a predisposing factor 2,6 Two laboratory studies, serumtryptase and urinary N-methylhistamine, are useful inconfirming anaphylaxis These tests must be obtained infairly close proximity to the reaction to be useful Forexample, tryptase levels peak 1 hour after anaphylaxis tobee stings and have a half-life in the serum of 2 hours 14 Similarly, urinary N-methylhistamine peaks 1 hour afterIV infusion of histamine and returns to baseline levelsafter 2 hours 14 Tryptase level does seem to correlate withseverity of the reaction 4 Furthermore, in cases of suspected fatal anaphylaxis, massively elevated ( > 50U/L) postmortem serum tryptase has been shown to be aspecific indicator of anaphylaxis 15 Causes of anaphylaxis are varied and are listed in Table 2 The discussion of each and every cause of anaphylaxis is beyond the scope of this report; however, ANAPHYLACTIC SHOCK / JOHNSON, PEEBLES 697 D o w n l o a d e d b y : U n i v e r s i t y o f W i s c o n s i n - M a d i s o n C o p y r i g h t e d m a t e r i a l